| Insurance IP

Bulletin

An Information Bulletin on

Intellectual Property activities in the insurance

industry

A Publication of - Tom Bakos Consulting, Inc. and Markets, Patents and Alliances, LLC |

April 15, 2008 VOL: 2008.2 |

||

| Adobe pdf version | Give us FEEDBACK | ADD ME to e-mail Distribution |

| Printer Friendly version | Ask a QUESTION | REMOVE ME from e-mail Distribution |

| Publisher Contacts

Tom Bakos Consulting, Inc.

Tom Bakos: (970) 626-3049 tbakos@BakosEnterprises.com Markets, Patents and Alliances, LLC Mark Nowotarski: (203) 975-7678 MNowotarski@MarketsandPatents.com Now Available Lincoln National Life Insurance Company Alleges Patent Infringement

- GMWB Lincoln National Life Insurance Company is the owner of three patents (one awaiting issue) and two additional patent applications which Lincoln believes cover the methods and processes used in providing the Guaranteed Minimum Withdrawal Benefits (GMWBs) prevalent in many insurers’ variable annuity products. Since GMWBs are such a common benefit

option or feature of variable annuity products offered by insurers in the

Tom Bakos (co-editor of the Insurance IP Bulletin) has prepared a comprehensive Intellectual Property Analysis of the Lincoln National GMWB family of IP. This analysis (over 200 pages of printed detail plus supporting documents on CD) represents well over 200 hours of review, analysis, and dissection of the specifications and claimed inventions. It points out prior art (believed to be relevant) either not disclosed or not considered by the USPTO on examination. It addresses the quality of the claims made. This analysis will be a valuable resource for anyone seeking a better understanding to the Lincoln claimed inventions. For

more information regarding this Analysis and how to acquire it, please go

to: Intellectual Property

Analysis (

http://www.BakosEnterprises.com/IPA).

The End of Insurance Patents? Question: I heard there is a court case that could end insurance patents. Is this true? Disclaimer:The answer below is a discussion of typical

practices and is not to be construed as legal advice of any kind. Readers are

encouraged to consult with qualified counsel to answer their personal legal

questions. Answer: Perhaps. The case is Ex parte Bilski. It is currently on appeal before the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC). Details: In 2002, Bernard Bilski and Rand Warsaw filed a patent application that disclosed a method for hedging risks associated with energy trading. Their method is not tied to any particular technology. The patent examiner rejected all claims under 35 USC 101 asserting that the invention was essentially an abstract idea. Bilski appealed. The Board of Appeals affirmed the examiner. Bilski appealed again, and now it is in front of the CAFC. This case has become a lightning rod for those that have strong feelings about the patentability of business methods. Thirty amicus briefs (i.e. outside legal opinions) have been submitted to the court with positions ranging from all business method patents should be banned as a violation of freedom of speech (ACLU) to all business methods should be patentable, no matter how abstract the invention is, since that is the future of our economy (professor Lemley of Stanford Law School et al.). Somewhat disturbingly, several major financial institutions, including MetLife, have submitted an amicus brief arguing that not only should abstract financial inventions not be patentable, but that the State Street Bank decision itself went too far and even technologically implemented financial inventions should not be patentable. It remains to be seen how the CAFC will rule. It further remains to be seen if the CAFC’s decision will be appealed to the Supreme Court. Prudent practice dictates, however, that in the meantime, anyone filing a patent application on a financial invention, such as a new insurance product, should say as much as possible in their application about the underlying technology required to practically implement the invention. Thus, even if the courts decide to roll the clock back and only allow patents on strictly technological inventions (e.g. computer systems) inventors can still get effective protection for their financial service inventions by patenting the advanced technological systems required to implement them.

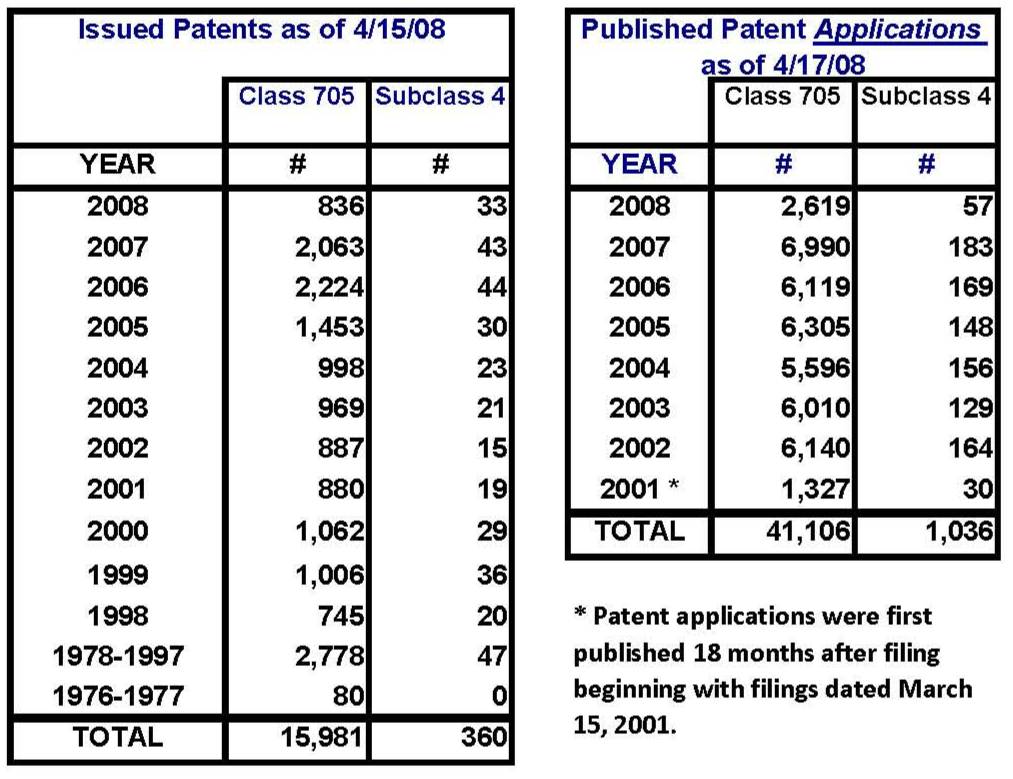

Statistics An Update on Current Patent Activity The table below provides the latest statistics in overall class 705

and subclass 4. The data shows issued patents and published patent

applications for this class and subclass.

Class 705 is defined as: DATA PROCESSING: FINANCIAL, BUSINESS PRACTICE, MANAGEMENT, OR COST/PRICE DETERMINATION. Subclass 4 is used to identify claims in class 705 which are related to: Insurance (e.g., computer implemented system or method for writing insurance policy, processing insurance claim, etc.). Issued

Patents Patents are categorized based on their claims. Some of these newly issued patents, therefore, may have only a slight link to insurance based on only one or a small number of the claims therein. The Resources section provides a link to a detailed list of these newly issued patents. Published Patent

Applications 29 new patent applications have been published during the last two months for a total of 57 during the first 3 ½ months of 2008 in class 705/4 indicating a continued high level of patent activity in the insurance industry. The Resources section provides a link to a detailed list of these newly published patent applications. Again, a reminder - Patent applications have been published 18

months after their filing date only since March 15, 2001. Therefore, there are many pending

applications that are not yet published. A conservative estimate would be that

there are, currently, close to 250 new patent applications filed every

18 months in class 705/4. The published patent applications included in the table above are not reduced when applications are issued as patents, rejected, or abandoned. Therefore, the table only gives an indication of the number of patent applications currently pending. Resources Recently published issued U.S. Patents and U.S. Patent Applications with claims in class 705/4. The following are links to web sites which contain information helpful to understanding intellectual property. United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) : Homepage - http://www.uspto.gov/ United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) : Patent Application Information Retrieval - http://portal.uspto.gov/external/portal/pair Free Patents Online -

http://www.freepatentsonline.com/ Patent Law and Regulation - http://www.uspto.gov/web/patents/legis.htm Here is how to call the USPTO Inventors Assistance Center:

Mark Nowotarski - Patent Agent services – http://www.marketsandpatents.com/ Tom Bakos, FSA, MAAA - Actuarial services – http://www.BakosEnterprises.com |

Introduction

The Statistics section updates the current status of

issued Our mission is to provide our readers with useful information on how intellectual property in the insurance industry can be and is being protected – primarily through the use of patents. We will provide a forum in which insurance IP leaders can share the challenges they have faced and the solutions they have developed for incorporating patents into their corporate culture. Please use the FEEDBACK link above to provide us with your comments or suggestions. Use QUESTIONS for any inquiries. To be added to the Insurance IP Bulletin e-mail distribution list, click on ADD ME. To be removed from our distribution list, click on REMOVE ME.

Thanks, FEATURE ARTICLE Enablement By: Tom

Bakos, FSA, MAAA Essentially, to satisfy the enablement requirement an

applicant must describe in the specification of a patent application “the

manner and process of making and using” the invention “in such full,

clear, concise, and exact terms as to enable any person skilled in the art

to which it pertains, or with which it is most nearly connected, to make

and use” it. An inventor is

therefore, required to disclose all of the non-obvious methods or

processes of making and using his or her invention in order to advance the

arts. In exchange for that

disclosure, the inventor gets a protected use of the invention for a

period of time – generally 20 years from the date of such

disclosure. The first paragraph of section 112 also requires that the specification contain two other things in addition to enablement:

These requirements are distinguished from the enablement requirement by their purpose. The purpose of a written description is to demonstrate that the inventor at the time the application was made had possession of the subject matter on which the claims were based. The best mode requirement is to encourage the inventor not to conceal from the public the preferred embodiment of the invention they claim to have made. That is, an inventor might be otherwise be encouraged to disclose only a second or third best embodiment to the public saving the best for himself. The invention to which this enablement disclosure

requirement applies is the invention defined by the claims. There may be other aspects of the

invention described in the written description of the specification but

the only invention subject to the enablement requirement is the invention

actually claimed. The level of disclosure required is that which is

sufficient for a person skilled in the art to make and use the

invention. Enablement has

been interpreted by the courts to mean can a person skilled in the art

make and use the claimed invention based on the disclosures provided in

the specification together with information known in the art without undue experimentation. In general, determining whether or not undue

experimentation is required to make and use an invention is highly

subjective and dependant on many factors which, well, make generalizing

difficult. And, for invention

in the insurance and broader financial services subject matter areas, even

greater subjectivity exists – in part, because most patent examiners have

little training or experience in these areas and making a judgment on

undue versus reasonable experimentation is determined from

the perspective of a person of ordinary skill in the art, a perspective

the examiner may not have. In

addition what “experimentation” means in the context of a business method

invention in the insurance or broader financial services areas may be

difficult to define. The need for one skilled in the art to experiment a bit in order to make and use the claimed invention does not invalidate a claim for lack of enablement – but undue experimentation would. How does one tell the difference? Well, one way to address this question is by factually considering the following:

Certainly, pricing an insurance product involves what

might be called experimentation in order to develop a premium rate that

satisfies pricing standards, covering expenses and benefits while

producing a profit. However,

since methods of pricing term insurance products are well known to a

person skilled in the art and the specification (let’s suppose) is not

suggesting that this pricing would be any different, then, I think, it

would be appropriate to conclude that this was not undue

experimentation. More simply,

it may comparable to “calculating a square root” or “screwing in a light

bulb”. On the other hand, if a claim step involved

“establishing a charge” for a new type of insurance benefit or guarantee

and a method for establishing such a charge was not described or even

hinted at in the specification, then a person skilled in the art might be

at a loss as to how to do such establishing without undue experimentation. This may be the case since there

are no known methods or processes for establishing such a charge and

similar methods do not exist in the subject matter area. If the financial impact or risk

associated with the occurrence of the insured contingent event which is

the subject of the claimed invention is new or unknown in the relative

art, then undue experimentation may be

required to figure out how to establish such a charge. There is no requirement that information be disclosed

in a specification that would result in a commercially viable or

commercially successful application of the invention. Thus, any lack of disclosure of

what might be considered undue experimentation to

produce such a commercial success would not count against

enablement. Only a failure to disclose undue experimentation required to make and use the invention, regardless of whether or not it would be commercially successful if made or used, would impact enablement. As noted above, experimentation routinely done in the development of insurance products which may include testing or trials during pricing (e.g. stochastic modeling) or confirming conformance with insurance law and regulation (which often requires discourse and negotiation with state regulators) is not a requirement for enablement. Such routine experimentation should be well within the skill set of a person of ordinary skill and there would be no need to disclose it. The purpose of the enablement requirement is to assure that how to make and use the claimed invention is communicated to the interested people with skill in the art in a meaningful way. In keeping with the section 112 requirement that such disclosure be “concise”, it is OK to interpret “concise”, meaning brief and to the point, from the perspective of a person skilled in the art. But, one caution is that a patent examiner looking at insurance business method specification language may not be skilled in the art. Therefore, since the examiner is the initial judge of enablement, using a lower standard than what a person skilled in the art would know when drafting specifications for insurance or financial services business method patent applications may be wise. In drafting claims in one’s own invention or if reviewing claims one may be accused of infringing, enablement is a characteristic one should check for. This is particularly true with respect to business method invention in the insurance and financial services areas since the patent examination process may not be as efficient in this subject matter area as in others. |