| Insurance IP

Bulletin

An Information Bulletin on

Intellectual Property activities in the insurance

industry

A Publication of - Tom Bakos Consulting, Inc. and Markets, Patents and Alliances, LLC |

December 15,

2005 VOL: 2005.5 |

||

| Adobe pdf version | FEEDBACK | ADD ME to e-mail Distribution |

| Printer Friendly version | QUESTION | REMOVE ME from e-mail Distribution |

| Publisher

Contacts

Tom Bakos Consulting, Inc.

Tom Bakos: (970) 626-3049 tbakos@BakosEnterprises.com Markets, Patents and Alliances, LLC Mark Nowotarski: (203) 975-7678 MNowotarski@MarketsandPatents.com Patent Study – A Foreign Perspective Protecting Innovation in the Financial Services Sector: A study of patent activity in UK Financial Services Industries By Prof Ruth Soetendorp, Dr Cornelius Alalade, Centre for Intellectual Property Policy & Management (CIPPM), Bournemouth University, UK This is a synopsis of a report published by Nottingham University Business School Financial Services Research Forum in 2004. The full report can be found at: http://www.cippm.org.uk/publications/publications.php?ID=19 Financial services sector players and the companies that serve their needs have a long history of patenting technical inventions. Our research asked to what extent is the UK financial services sector aware of, or interested in, patenting business methods? As there is no robust definition of a business-method patent, we were interested in any patents that related to methods of doing business. Questionnaires were issued to 134 financial services companies, addressed to the Company Secretary. 16% responded, coming in almost equal numbers from small and big players. They indicated a low awareness of patenting as a commercially significant issue.

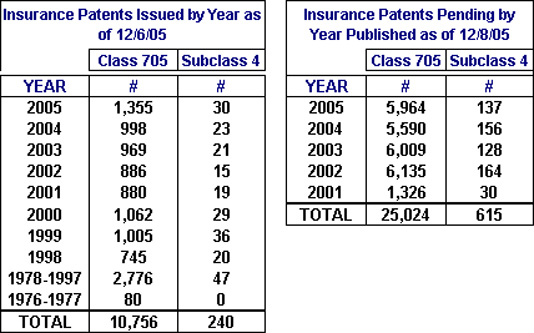

UK companies are more averse to patenting than their US counterparts, and financial services companies appear to be more averse than other sectors. UK financial services companies would be advised to consider the suitability of patent protection for innovative products and processes. The sector needs to keep a watching brief on financial service patent activity outside Europe, because it is important to ensure that Europe does not lose out competitively in world terms. Patent Q & A "Swearing back" at the patent office? Question: If I write down my idea and have it notarized, does that protect me until I can get a patent application filed? Disclaimer: The answer below is a discussion of typical practices and is not to be construed as legal advice of any kind. Readers are encouraged to consult with qualified counsel to answer their personal legal questions. Answer: It can help in some limited cases, but if it’s an important idea, you should file at least a US provisional patent application as soon as possible. Details: There is a common misconception that if you can prove that you are the original inventor of an invention, then you deserve to get a patent. This is not necessarily true. Patents are granted to inventors by national governments in order to promote the welfare of their respective nations. The theory behind this is that the general welfare of given society will be improved if inventors are encouraged to publicly disclose critical aspects of their inventions that they would otherwise keep secret. Patents provide encouragement for this public disclosure by granting limited monopoly rights to inventors for the new and non-obvious aspects of their inventions that they describe in their patent applications. Generally, if an invention has already been disclosed to the public before a patent application is filed, then there is no longer any need for a government to provide any incentives to redundantly disclose the invention. Whether or not an inventor can "prove" that they were the one that made the original invention is irrelevant. For almost every country in the world, an inventor is "barred" from getting a patent once the invention becomes public. The critical exception is the United States. The United States grants a one-year grace period from when an invention first becomes public to when an inventor has to file their patent application. If, in the course of examination of a patent application, a patent examiner cites a reference that predates the filing date2 of said patent application by less than a year, then an inventor may still get a US patent if he or she can "swear back of the publication date3" of said reference. In order to effectively swear back of a reference, an inventor submits a petition to the US patent office along with written evidence to show that they fully conceived of the invention before the effective date of the reference and that they were "diligent" in either "reducing the invention to practice" or filing a patent application4. This is where the notarized document is important. A notarized document can serve as evidence of when an invention was first conceived. A paper that is signed, dated and preferably witnessed can also serve as evidence. A written "declaration" by a witness can also be adequate evidence. Similar evidence may be used to satisfy the diligence requirement. It can be very difficult to demonstrate diligence. The inventor, for example, must work continuously on the invention. If the inventor works on another invention before the first one is reduced to practice, that destroys the continuity and the inventor is deemed to not have been sufficiently diligent to be entitled to a patent. Many other restrictions apply as well. It is important to consult a licensed patent attorney or agent to get all of the details. In summary, governments grant patents to encourage inventors to disclose the secrets behind their inventions. If the secrets become public knowledge before a patent application is filed, then in most countries of the world, an inventor looses their patent rights. An important exception is the United States. In the United States, an inventor can "swear back of a reference" by submitting evidence that they conceived of the invention before the effective date of the reference and were diligent in either reducing the invention to practice or filing a patent application. Swearing back of a reference can be very important in preserving an inventor’s US patent rights, but an inventor should still strive to file at least a US provisional patent application as soon as they have fully conceived of their invention. StatisticsAn Update on Current Patent Activity The table below provides the latest statistics in overall class 705 and subclass 4. The data shows issued patents and published patent applications for this class and subclass.

Class 705 is defined as: DATA PROCESSING: FINANCIAL, BUSINESS PRACTICE, MANAGEMENT, OR COST/PRICE DETERMINATION. Subclass 4 is used to identify claims in class 705 which are related to: Insurance (e.g., computer implemented system or method for writing insurance policy, processing insurance claim, etc.). Issued Patents Since our last issue, 6 new patents with claims in class 705/4 have been issued: 3 relate primarily to L&H and 3 are, primarily, P&C. All but one has an assignee indicated. Patents are categorized based on their claims. Some of these newly issued patents may have only a slight link to insurance, therefore, based on only one or a small number of the claims made. The Resources section provides a link to a detailed list of these newly issued patents. Published Patent Applications Twenty seven (27) new patent applications with claims in class 705/4 have been published since our last issue. They are broken down by product line or type area as follows:

Health:

8 The Resources section provides a link to a detailed list of these newly published patent applications. Again, a reminder - Patent applications have been published 18 months after their filing date only since March 15, 2001. Therefore, there are many pending applications not yet published. A conservative assumption would be that there are about 150 applications filed every 18 months in class 705/4. Therefore, there are, probably, about 625 class 705/4 patent applications currently pending, only 473 of which have been published. Because the pending patents total above includes all patent applications published since March 15, 2001, applications that have been subsequently issued will also appear in the issued patents totals. ResourcesRecently published issued U.S. Patents and U.S. Patent Applications with claims in class 705/4. The following are links to web sites which contain information helpful to understanding intellectual property. United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) : Homepage - http://www.uspto.gov/ United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) : Patent Application Information Retrieval - http://portal.uspto.gov/external/portal/pair Free Patents Online - http://www.freepatentsonline.com/ World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) - http://www.wipo.org/pct/en Patent Law and Regulation - http://www.uspto.gov/web/patents/legis.htm Mark Nowotarski - Patent Agent services – http://www.marketsandpatents.com/ Tom Bakos, FSA, MAAA - Actuarial services – http://www.bakosenterprises.com |

In this issue our feature article, Is It a Better MouseTRAP?, provides guidance on how to overcome the problems of getting genuinely new insurance products approved by state insurance departments, especially when the products are so unique that there may not be a category for them. For our UK readers we provide a summary of a recent study by Bournemouth University on patent awareness among the UK financial services sector, including insurance companies. UK financial services companies acknowledge that innovation is critical to their future success, but are still largely unaware of how patents can protect that innovation. Our Q/A section discusses the benefits of having an initial idea notarized to preserve an inventor’s patent rights. It can help in certain limited situations, but it’s better to file a provisional patent application as soon as possible. In the Statistics section we provide links to the latest issued US patents and published patent applications the insurance class (i.e. 705/004). We wish our readers a happy holiday season and we’ll be getting back to you next year. Our mission is to provide our readers with useful information on how intellectual property in the insurance industry can be and is being protected – primarily through the use of patents. We will provide a forum in which insurance IP leaders can share the challenges they have faced and the solutions they have developed for incorporating patents into their corporate culture. Please use the FEEDBACK link above to provide us with your comments or suggestions. Use QUESTIONS for any inquiries. To be added to the Insurance IP Bulletin e-mail distribution list, click on ADD ME. To be removed from our distribution list, click on REMOVE ME.

Thanks, FEATURE ARTICLE A Better MouseTRAP? By: Tom Bakos Do you really have a better mousetrap … or, is what you have just invented more like a mouse feeding station? That is, your brilliant idea, which you have developed into a patentable machine, is a humane way to get mice out of your house. It attracts them out of your house through a one-way door to a feeding tray with some of the best cheese and peanut butter essence a mouse will ever find. It works great but is it a mousetrap? If there were any laws or regulations regarding prior approval of mousetrap design before a better mousetrap could be sold, you might have to embark on a long and difficult process of clearing a path to your door before you could sell it. Innovation in the field of insurance works the same way except there are laws and regulations that define what insurance is and isn’t. These laws and regulations won’t, necessarily, affect whether or not you can get a patent on your idea but they may affect whether or not your insurance business method invention that defines a new type of insurance or a new and better approach to solving an insurance problem gets off the ground. Defining Insurance—The Basics Thinking like an inventor, one would like to have as broad a definition of insurance as possible that is not overly broad. That is, one wants a definition that captures the "essence" of insurance and nothing more. The following definition contains all of the essential elements: Insurance is a process through which the financial consequences of a contingent event are transferred from one entity to another for the payment of a premium. This definition has all of the essential basic elements: a contingent (or insured) event; an insurer; an insured; and a premium. A contingent event is an event that is uncertain with respect to its occurrence, timing, or severity. That is, a contingent event is uncertain with respect to any one or more of these factors. The uncertainty of the event occurring implies that the insured entity generally has no control over the occurrence of the event, its timing, or its severity. Another word used to describe this is: "fortuitous". Uncertainty is an important characteristic for insurable contingent events. The more certain an event is, the less insurable it is, generally. For example, often the financial consequences of pregnancy are insured although "pregnancy," per se, is not considered an insurable event since it is not really uncertain with respect to its occurrence or timing. However, since there is uncertainty surrounding the severity of its financial consequences, insurance is more likely to be provided for complications resulting from pregnancy. In general, the uncertainty of an event implies that it is insurable and that insurance may be necessary in order to offset adverse financial consequences. This is supported by, for example, New York Insurance Law §1101 wherein it states: (1) "Insurance contract" means any agreement or other transaction whereby one party, the "insurer," is obligated to confer benefit of pecuniary value upon another party, the "insured" or "beneficiary," dependent upon the happening of a fortuitous event in which the insured or beneficiary has, or is expected to have at the time of such happening, a material interest which will be adversely affected by the happening of such event. (2) "Fortuitous event" means any occurrence or failure to occur which is, or is assumed by the parties to be, to a substantial extent beyond the control of either party. And, since insurance law and regulation tends to be reactive (perhaps much like law and regulation, in general), allowable and non-allowable types of insurance is often rather specifically defined. For example, the statutes of most states recognize as "types of insurance" the following broad categories: Life; Health; Property; Casualty; Surety; Marine; and Title. An innovative new "kind of insurance" might have some difficulty fitting in under these broad statutory categories and the more detailed subclasses provided for in law. For example, the insurance of glass "against loss or damage from any cause" is a form of casualty insurance anticipated under many state statues. However, the insurance of a sheet plastic glass substitute like Plexiglas®, for example, is not mentioned in the law under "kinds of insurance." This could be a problem – not for patentability but for the practical application of an invention that is designed to provide a system for insuring glass substitutes. Consider the development of variable life and annuity products (VUL) that had their beginnings in the late 1960s but didn’t find commercial success until the mid-1980s. The VUL product concept serves as a good historical example that new product design can stretch the concept of what insurance is. VUL, in particular, infused life and annuity insurance products with even more investment than they ever had before. The pushing of the investment border in insurance products, lead to the addition of a "definition of life insurance" to U.S. tax law (IRC §7702). This definition marked, in tax law, the line between an annuity type "investment" and "life insurance". Insurance product innovators must now contend with this on the life insurance side of the business. So, what is an inventor to do when faced with a non-accommodating regulatory structure? That is a hard question to answer without the specifics but some general guidelines might be applied.

For example, New York §1113 in which "kinds of insurance authorized" are defined has 31 paragraphs. Paragraph 31 provides such a catchall category: (31) "Substantially similar kind of insurance," means such insurance which in the opinion of the superintendent is determined to be substantially similar to one of the foregoing kinds of insurance and thereupon for the purposes of this chapter shall be deemed to be included in that kind of insurance. If an invention enables a "substantially similar kind of insurance" it may fit. The inventor will probably have to make an effective argument to insurance departments to assert this point.

For example, a new, inventive Long Term Care benefit structure designed to lower LTCi premium levels may not comply with all current state regulation regarding nursing home benefits but can be applied to care received at home. This may not be ideal, but it is a start and, if successful, may prompt revision in the law to accommodate a broader application of a desirable new feature.

A lesson to take away from this is that it is just as important to be aware of and begin addressing the regulatory approval aspects of any new approach to solving an insurance problem as it is patentability issues. [1] Frey, Joe, “Progressive’s “pay-as-you-drive” Auto Insurance Poised for Wide Rollout”, www.insure.com, July 18, 2000 [2] Or more precisely, the “priority date” of said patent application. [3] Or more precisely, if they swear back of the“effective date” of said reference. [4] Filing a patent application is known as a “constructive reduction to practice”. |